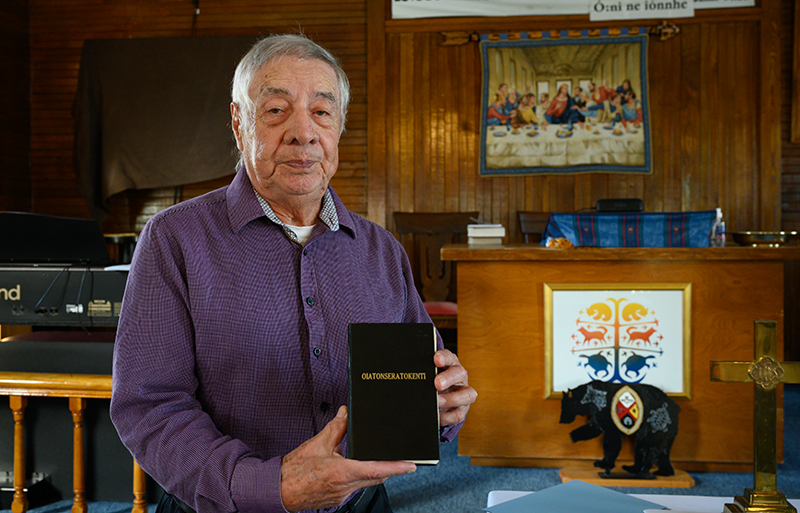

Wrapped in the purple of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and printed on pages as thin and delicate as onion peels, Ohiatonhseratokénti: The Holy Bible in Mohawk hearkens back to a different era for the language, when Sosé Onasakenrat of Kanesatake, a reverend, translated the four gospels in the mid-1800s.

Onasakenrat’s great-grandson, Harvey Satewas Gabriel, grew up immersed in this legacy as a first-language speaker and devout Christian. The 83-year-old made it his mission over the past two decades to finish what Onasakenrat started.

Gabriel traces the feat back to 1957. This is the year he first heard Kanien’kéha read aloud at church, when community member John Angus, an ordained minister of the United Church, was invited to deliver a service in Kanesatake.

“I used to go to church and there would be a white minister at the pulpit who’d be speaking only English. But reverend John Angus, when he started the service, it was all in Mohawk. That was like honey to my ears because I never heard any ministers speak Mohawk at the pulpit,” he said.

He was amazed as Angus translated Bible scripture on the spot from the English into Kanien’kéha as he read to the congregation.

When Gabriel got home, he asked his mother why there was no Kanien’kéha Bible. She replied it would be a big project. Who was going to do it?

Those words planted a seed that sprouted in 1974 as he mowed his lawn: he would do it himself.

He planned to spend his retirement on the project, but in 1999, a group was formed to translate second Corinthians, a process in which Gabriel participated. It included Doris Montour, Josie Horn, Charlotte Provencher, Madeline Montour, and Mavis Etienne.

When he retired in 2005, he began translating the remaining books – all 58 of them – in earnest.

He frequently referred to Webster’s Dictionary to make sure he understood the nuance he needed to capture, determined to ensure his text captured the richness of Kanien’kéha.

“My language is my identity,” said Gabriel. “If somebody comes to me, I tell them who I am. I am a fluent Mohawk speaker. That’s the highest point for me.”

He worked with biblical scholars to ensure the quality of the translation, even translating his words back into English to demonstrate their fidelity to the Bible.

“This wasn’t just this guy sitting in his basement writing what he thought. The Canadian Bible Society was in there doing quality control of this with biblical language experts and academics who had been working with him over the years, just making sure there was the quality of the translation,” said Royal Orr, a board member of the United Church of Canada Foundation, which played a major role in funding the project in recent years.

Source: The Eastern Door